How practical and digitally implementable laws are developed

Over 90% of new federal laws now use elements of Digitalcheck. This is a new record. For the Digitalcheck team under the auspices of the Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community (BMI), this means that a lot of case studies and real laws have now been created with the help of the Digitalcheck instruments. BMI, the National Regulatory Control Council (NKR), and DigitalService have reviewed the regulatory projects and identified best practices. These examples illustrate which methods, skills, and processes contribute to the development of legislative projects that can also be implemented digitally and with little bureaucracy in practice – saving time and money in the process.

Much more than just a checklist

The background: since 2022, DigitalService has been working on behalf of and with BMI to develop suitable instruments for digital-ready legislation, all unified within our Digitalcheck project. Digitalcheck is by no means “just” a checklist. Instead, it integrates methods, tools, and support measures from across various digitalization domains that help policy drafters ensure good implementation in practice when drawing up new legislation.

Since 2023, there has been a requirement to apply Digitalcheck for legislative proposals, which means that the tools for digital-ready legislation have now been used in respect of a multitude of laws, regulations, and provisions. We highlight some particularly good examples in this post – the Electricity Duty Act or StromStG (Federal Ministry of Finance, BMF), the Building Construction Statistics Act or HBauStatG¹ (Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development, and Building, BMWSB), and revised aviation law (Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport, BMDV). In all of these regulatory projects, methodology for digital-ready legislation has proven particularly effective.

According to the regulatory impact assessments of the ministries involved, the following improvements have been achieved through the digital implementation:

- The introduction of automated processes for the electricity duty means that a much higher application volume can be handled. This is relieving the strain on the administrative assistants in the main customs offices responsible for the implementation. The Act has brought forward the online application requirement to 2025, and will reduce implementation costs by 15.4 million euros per year (source: Position No. 7115, German only).

- In the revised aviation law, a new framework has been established for the automated processing of drone applications. This is crucial in ensuring the high volume of applications is dealt with in an expedient manner and in avoiding considerable delays in issuing approvals to the general public. According to NKR, the automation means an annual saving of 2.8 million euros for the Federal Aviation Office (LBA) (source: NKR Position No. 7083, not publicly available at this time).

- Consistent re-use of data is ensured through consideration of the once-only principle within the Building Construction Statistics Act. This saves citizens around 51,000 hours of their time each year, which equates to some 1.275 million euros in monetary terms. The business sector also benefits – with an annual reduction in costs associated with red tape of some 770,000 euros (source: Position No. 6968, German only) Despite the initial effort involved for administrations in making the switch, the long-term benefits outweigh the disruption.

These examples show that administration efficiency has been increased and the needs of target groups are being met more swiftly.

We look below at how the methodology and aids for digital-ready legislation were used in these specific cases to achieve the desired outcomes.

Principles set the course for implementation

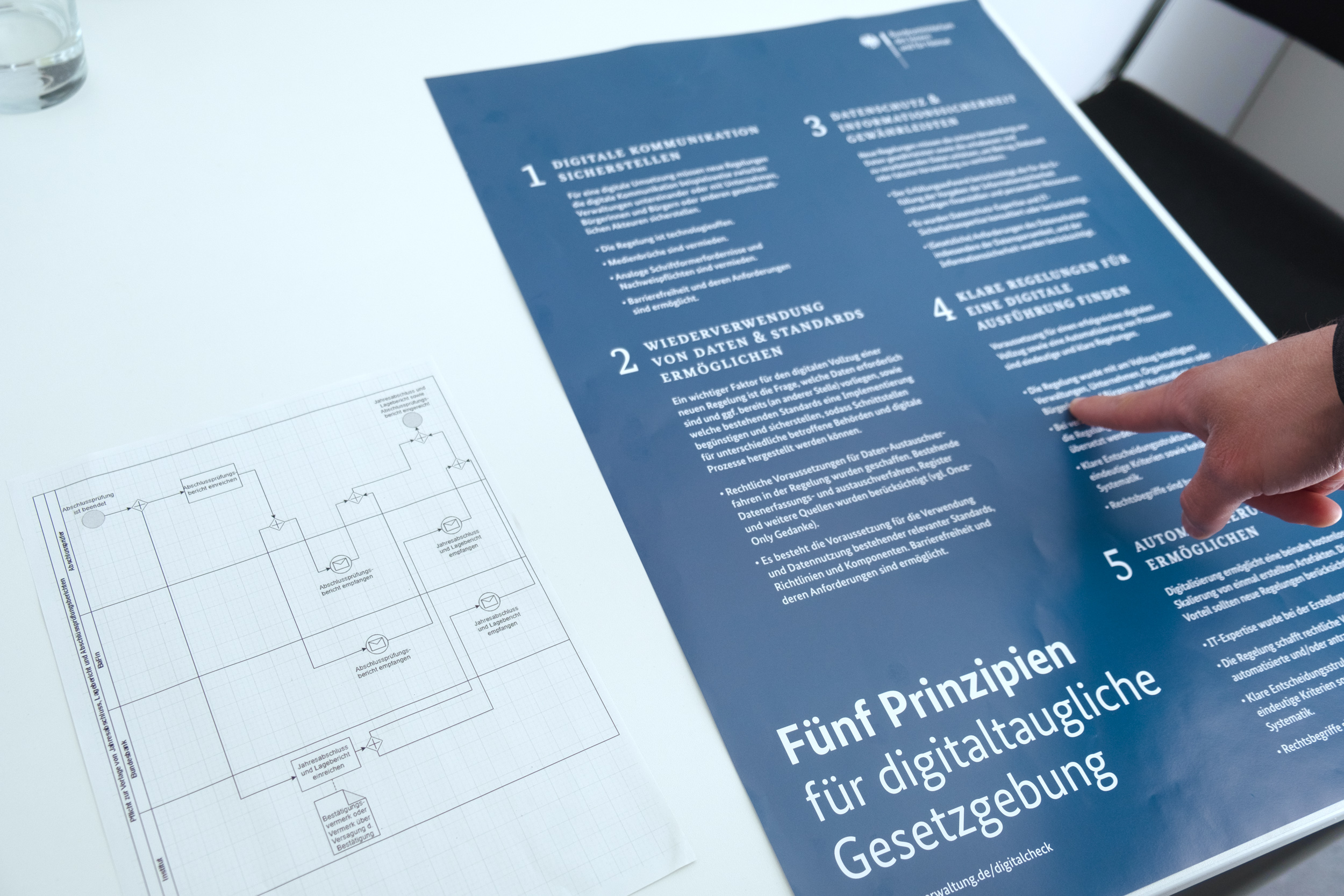

At NKR, the five principles of digital-ready legislation serve as the basis for assessing digital readiness. The Digitalcheck documentation states: “Use the five principles for digital-ready legislation when working on regulatory projects.”

The five principles are: 1. Ensure digital communication, 2. Enable re-use of data and standards, 3. Ensure data privacy and information security, 4. Set clear rules for digital implementation, and 5. Allow automated processes.

We describe the five principles, the idea behind them, and their function here: “Digitalcheck: Five principles for digital-ready legislation.”

The Building Construction Statistics Act consistently implements the once-only principle (Principle 2). In practical terms, this means that the legislation permits the use of information already available to building supervisory authorities. In addition, the data collected is accessible to municipal statistical bodies, who operate a shared evaluation database for publications. The legislation also implements Principle 5 (“Allow automated processes”). Instead of developers submitting physical documents to the statistical authorities, as had been the case previously, the information is now recorded digitally in a structured and machine-readable format using the xBau standard.

The same applies to the drone regulation – according to the relevant policy officer, the five principles proved helpful in drafting legislation with a more execution-driven approach and including important aspects of digital implementation in the explanatory statements. As a result, automatic data transfer has been enabled and a payment system integrated so that decisions on costs, operator numbers, and certificates of competence can be issued digitally. For these and other reasons, NKR considers the project a positive example of the successful automation of administrative records.

To facilitate good implementation of the five principles, Digitalcheck recommends visualization and involving stakeholders at an early stage. The regulatory projects highlighted here are also good examples of this.

Visualization reveals opportunities for digitalization

Specifically, the Digitalcheck documentation states: “Visualize the implementation of the policy plans before ever working on the text so that you can identify aspects of digital readiness at an early stage and incorporate these when drafting the proposed law.”

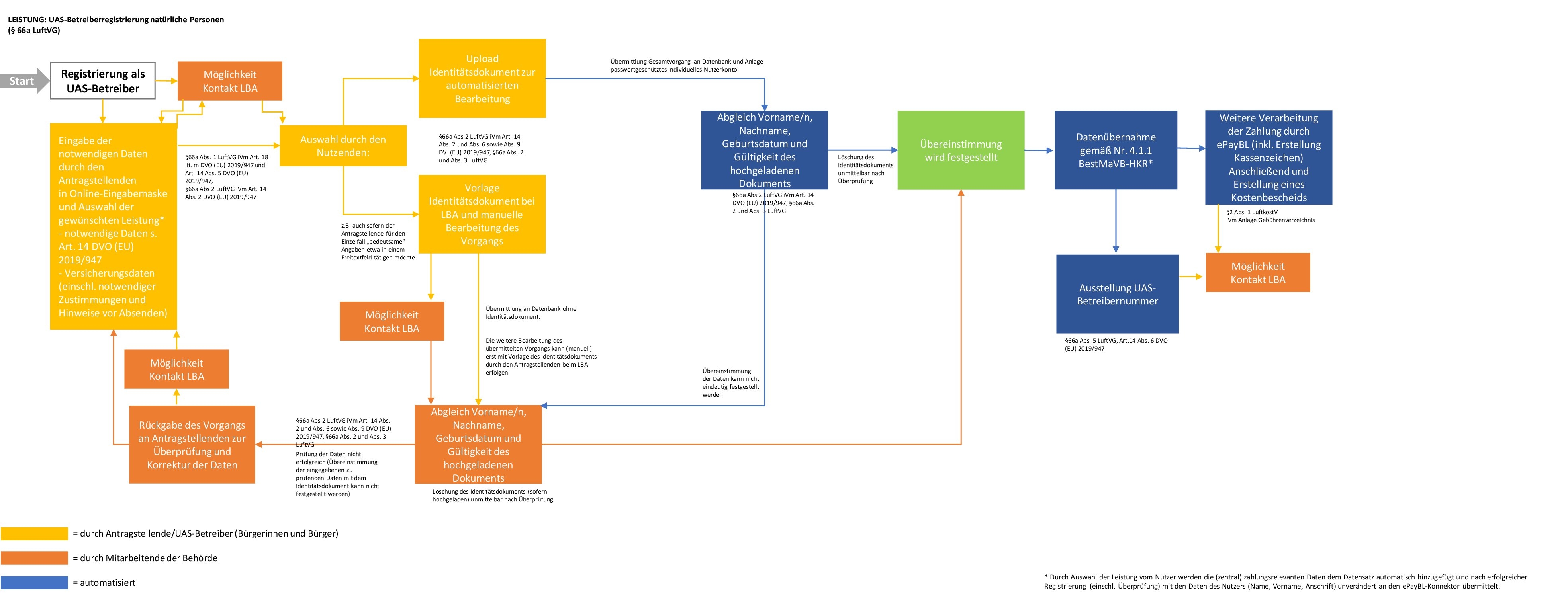

The Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport (BMDV) placed particular emphasis on visualization when drafting the amendments to aviation law. For example, it set out the EU certificate of competence for piloting drones – almost like a drone driving license – and the operator registration process in a visualized format.

The visualization created within the framework of the amendments to aviation law depicted the drone registration process for natural persons. You can download the visualization here to get a better idea.

The first drafts for this came from the Federal Aviation Authority (LBA). It has already been using visualization for quite some time in its work and was able to immediately apply the methodology. This represented a real benefit for the Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport: the policy officers gained additional insights into the challenges of implementation. “I noticed in exchanges with the LBA that processes were illustrated much more clearly [through the use of visualization], especially for a legal practitioner like me who does not have practical implementation experience,” explained a policy officer at the ministry. The policy officers could use the LBA’s visualization and add a legal perspective. NKR emphasized the positive role of visualization in its position on the revision of the Aviation Act, stating that it made processes and system contexts more transparent and revealed opportunities for further digitalization. As a consequence of the use of visualized formats, NKR was able to recommend increased utilization of authentication platforms already in place, such as Bund ID developed by BMI and the organization account for legal entities – further implementation options that might have gone unnoticed without such visualization.

The Act on Modernizing and Reducing Bureaucracy in Electricity and Energy Duty Legislation, or the Electricity Duty Act for short, is another example of best practice for the successful integration of visualization. BMF policy officers worked together with the Digitalcheck team to create detailed data flow charts, decision trees, and roadmaps. In addition to illustrating the processes concerned, the visualizations also allowed for comprehensive analysis so that switches between media and opportunities for automation could be identified. Visualization made the processes easier to grasp and simplified consultation with the various stakeholders. Finally, the visualizations were included in the draft act (draft act, p. 134–136), making this a true example of transparency and understandable legislation. For more on this example, please see the associated blog post.

It is important to note that fancy designs and special tools are not essential to producing a good visualization (see illustration). What matters is presenting the specifics in a simplified way – even with PowerPoint. It must be possible to discuss the processes, so it is crucial that they are clearly illustrated.

Insights into daily practice from implementing authorities

The Digitalcheck documents also state: “Include other perspectives: speak with the people who will implement your proposed legislation and will be affected by its implementation.”

When working on the Aviation Act, BMDV liaised with those who would feel its practical effects. BMDV discussed with the LBA how best to apply the Digitalcheck principles in the interests of users. The ministry recognized that the LBA, as the authority that would implement the legislation, had a particularly good understanding of the needs of the citizens and organizations involved because of its regular contact with them.

There has already been a relationship and communication between the Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development, and Building (BMWSB) and the Federal Statistical Office for years. When reforming the Building Construction Statistics Act, the specialist department at the Federal Statistical Office applied the five Digitalcheck principles to the regulation to evaluate the digital aspects for the ministry. Among other things, the relevant policy officer described how available data could be re-used (Principle 2) and how clear rules for digital implementation should be drawn up (Principle 4). Individual sections of the legal text were formulated in collaboration on this basis. In addition, ministry staff discussed the legal text with the authority and both parties jointly drafted specific provisions. As the authority’s requirements were already considered at the drafting stage, there was no need to subsequently rework the text. NKR also emphasized the positive impact of this in its position. In summary, BMWSB not only considered the needs of the Federal Statistical Office, but also gave colleagues there the opportunity to help shape the legislation. As a result, the project has reduced the reporting burden as well as the duty of disclosure for citizens and organizations – all in all, a worthwhile, meaningful, and time-saving collaboration.

Both projects show what can be achieved when authorities and other stakeholders involved in implementation work closely together from an early stage. By making legislation easier to understand and enforce and also incorporating a greater variety of perspectives, such collaboration is conducive to a digital, and therefore practical and streamlined, implementation.

Having said all that, there is still room for improvement. While the supports in Digitalcheck, as adopted by the federal cabinet, recommend involving citizens, organizations, associations, and experts at an early stage, this approach is not yet additionally enshrined in the Joint Rules of Procedure of the Federal Ministries (GGO) and is often bypassed due to the pressure of deadlines. The options are still limited and resources are insufficient. Close cooperation between stakeholders involved in implementation and specialist departments is by no means the norm, and there are few formats that facilitate early participation.

Greater integration of digital competence

As we can see from the three regulatory projects looked at here, the Digitalcheck methods and support services developed under BMI’s leadership in recent years are promoting the digital implementation of regulatory projects. The examples illustrate in very concrete terms that digital readiness is a crucial factor for accelerating processes, reducing costs, and avoiding red tape. In an international context as well, the federal government’s approaches to ensuring legislation is increasingly digital-ready are considered shining examples. The European Commission, for example, is using the Digitalcheck review logic and content as a guide for the introduction of interoperability assessments. See: Better regulation for smoother implementation.

There is still a long way to go to achieving a comprehensive change in legislative practice. The increasing complexity of regulatory issues means that practical competence in IT, service design, and data and product management is needed to complement the legal expertise within ministries. Implementation task forces could be set up at short notice for projects whose success depends to a high degree on digital implementation, so that the relevant expertise can be included in legislative processes. At the same time, it is essential that departments continuously develop methodological and digital expertise for the long term, and thereby ensure the efficient, digital implementation of projects.

Markus Richter, Federal Government Commissioner for Information Technology (source: Aktueller Sachstand zum Digitalprogramm BMI, Germany only)

We can see from firsthand experience with Digitalcheck that ensuring legislation is digital-ready and suitable for practical implementation will be an ongoing responsibility of the federal government beyond the scope of the project, as a fundamental shift in legislative work is needed and should be supported and perpetuated through the application of suitable measures and instruments.

¹: There are currently concerns about the practical implementation of the law. While automation is legally feasible, it is not yet practicable. This is because the “xBau” standard has not yet achieved the necessary level of technical maturity and therefore cannot be applied in practice.

Read more on the topic